You can find Dr. Billaeur’s excellent article here.

The data comes from the US Uterus Transplantation Consortium, the US centers providing this medical treatment [1]. Over the past five years, they have performed 33 uterine transplantations resulting in 21 live births. All study participants had “absolute uterine factor infertility” – the absence of a uterus. Here are their aggregated results.

Recipients – 31 had a rare genetic disorder, Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome, where the vagina and uterus fail to develop correctly, but the women have normal ovarian function and external genitalia. Two had a prior hysterectomy, the surgical removal of their uterus. Mean age 31, mean BMI 24. Six “had at least 1 child (through adoption, gestational carrier, or marriage) prior to uterus transplant.”

Donors – 21 non-directed live donors and 12 dead donors. 93% of the donors had one or more full-term live births, 7 having had C-sections. Donation was not without risk; 23% of live donors experienced a complication requiring further surgical, endoscopic, or radiologic intervention. For comparison, the rate of these types of complications among kidney donors is between 3-6% [2]

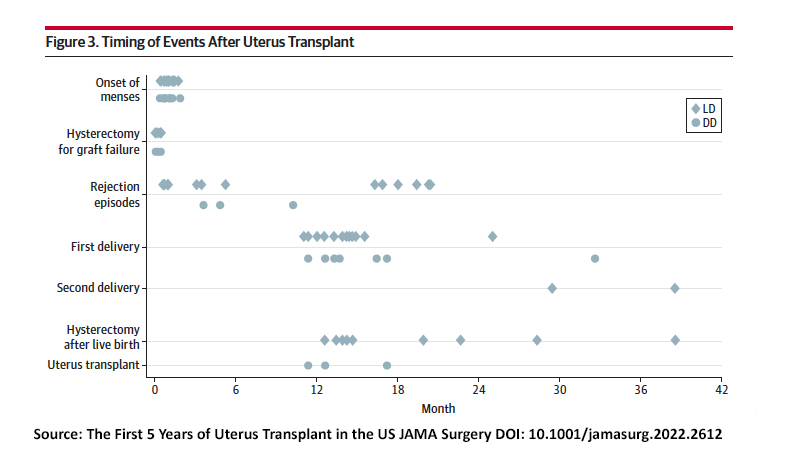

Some surgical details –the metric of successful uterine transplantation is the ability to achieve a live birth. Still, as the researchers report, “technically successful transplant (a viable graft at postoperative day 30) is an essential milestone.” 76% of these procedures were successful at 30 days with no further failures at one year. There were no differences in losses due to the status of the donor as living or dead. For context, the far older kidney transplantation procedure has a success rate of 92%. The percentage of live births overall was 58%, but when considering only the transplants surviving a year or more, that percentage increases to around 80%.

Surgical complications – in the 24% whose transplants were unsuccessful, most were due to vascular causes and occurred within the first week or two. [3] 30% of these iatrogenically immunocompromised recipients experience an infection, primarily urinary tract infections. For those that just need to know, there were 3 COVID infections (one in a recipient vaccinated with two doses) with no downstream adverse effects on the mother or baby. Finally, the site where the uterus is surgically reconnected to the vagina is prone to narrowing (stricture formation). Access to this area to do biopsies for rejection are essential in managing these patients and is hindered by stricture formation. 72% of recipients had some degree of narrowing; half required further surgical intervention, and half were able to “self-dilate” the area.

Acute cellular rejection or ACR is the most common cause of transplant rejection. Ten recipients with one-year graft survival experience this complication, most responding to an additional cycle of steroids.

“Pregnancy following uterus transplant relies on assisted reproductive technology….”

First, embryos need to be created through in-vitro fertilization. These frozen embryos are then transferred into the uterine transplant, a mean of six months later. Twenty-three recipients underwent 59 embryo transfers, resulting in 19 live births, a success rate of 38%. For context, for women in this age group with a normal uterus, embryo transfers are successful about 70% of the time.

Pregnancy was complicated by gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, and pre-eclampsia. While hypertension and diabetes might result from the steroids taken to prevent uterine rejection, preeclampsia reflects additional kidney damage. In all instances, the incidence was far higher than for pregnant women without uterine transplants.

The median time from transplantation to a live birth was 14 months. All births were by C-section, and 63% were performed before 37 weeks because of maternal concerns. Half of the babies were born after 36 weeks, half before. Their median birth weights placed them in the 58th percentile, and the median time in the neonatal intensive care unit was 18 days for roughly half of the births. There were no congenital malformations.

“After a successful outcome (live birth of at least one child), recipients undergo a graft hysterectomy.”

I didn’t know that, although it makes intuitive sense. If the purpose of the uterine transplant is to have a live birth, then why continue with immunosuppressive treatment after your goal is met? That also helps explain the short interval between the uterus's transplantation and subsequent embryo transplantation. The timing of graft hysterectomy is based on patient preference and the risk of immunologic or maternal complications. 57% underwent hysterectomy at the time of C-section; of those, 60% were medically indicated, and 40% were patient preference. The median time to hysterectomy was 15 months post transplantation.

This complete but early data suggests that we have a new child-bearing option for women without a uterus, a small group, roughly 0.02% of women – with an “orphan” disease. Uterine transplantation is feasible, resulting in a significant number of live births. It comes with risks to donors and recipients. The long-term impact on the children remains unknown.

[1] Baylor, Cleveland Clinic, and the University of Pennsylvania

[2] Comparison with other transplant participants is always an apples-to-oranges affair, but the comparison provides at least some qualitative measure.

[3] As a vascular surgeon, I found this interesting, especially the remarks on which veins were used in the reconstruction, which I suspect was the source of most of the vascular occlusions. Sewing two veins together is tough; like sewing two pieces of wet tissue paper together, it requires a very gentle set of hands.

Source: The First 5 Years of Uterus Transplant in the US JAMA Surgery DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.2612