Vasomotor Symptoms

Talking about the hot flashes associated with menopause may open me to mansplaining, but that is the chance I take. Menopause, the cessation of menstrual periods greater than a year, is a natural biological process characterized by a depletion of ovary-produced estrogens. Loss of these estrogens from surgical removal of the ovaries or medical suppression of estrogens in the case of breast cancer also can elicit vasomotor symptoms (VMS).

VMS involves increased blood flow to the skin, resulting in elevated skin temperature and a feeling of uncomfortable warmth. It may be accompanied by palpitations, anxiety, or sweating. It can be debilitating.

- 75% of menopausal women and 50% of breast cancer patients experience VMS

- In at least one study, women have reported VMS to last a median of 7.4 years

- Both the frequency and intensity of symptoms can vary, from once a day to once an hour and from mild to severe, respectively. [1] As we should expect, these symptoms are heterogeneous when stratified by race or ethnicity. Black women “experience increased severity and duration of VMS symptoms compared to White women,” Chinese women have the shortest duration of symptoms. …Native American women may have the highest prevalence of VMS.”

- A “majority of female workers ages 45 to 55 said symptoms of menopause interfered with work and a third of those surveyed women reported missing time from work due to menopause symptoms.”

- Both clinicians and patients believe that the symptoms are underrecognized and that the treatment options are limited, especially for those not opting for hormonal replacement therapy. A recently published study found that only about 30% of Obstetrics and Gynecology residents had any training or experience caring for menopause.

What causes VMS?

The short answer is the depletion of estrogens, which is why hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) has been the standard of care for years. HMT is not without its issues, a point we will return to later.

The long answer is that various factors drive VMS symptoms and severity. Leaving aside the effects of obesity, smoking, and lack of exercise, pharmaceutical companies have keyed in on physiologic changes in the hypothalamus, the center of our regulatory control of body temperature.

“Inside the thermoregulatory center in the hypothalamus, specific neurons, known as kisspeptin/neurokinin B/ dynorphin (KNDy) neurons, contribute to regulation of the body’s temperature. KNDy neurons are inhibited by estrogen and stimulated by the neuropeptide neurokinin B (NKB) in a delicate balance.”

In menopause, NKB is increasingly unopposed, which in turn increases the actions of the KNDy neurons. These neurons signal the body to dissipate heat, resulting in the symptoms of VMS.

Treatment

As I mentioned previously, the standard treatment for VMS has been hormonal replacement of estrogens (HRT). While the risks are low, HRT has been associated with an increased incidence of breast and ovarian cancer, cardiovascular disease, including heart attacks and stroke, and pulmonary embolism. It is clearly contraindicated in women developing VMS after medically induced estrogen reductions because of cancer. And once again, these risks are heterogenous. Black women are more inclined to VMS and more likely to have HRT-associated heart risk, whereas in White women, HRT is protective of heart disease. Black women have a more significant mortality due to breast cancer.

For women opting for non-hormonal therapy, there are two pharmacologic options. Low-dose paroxetine, an anti-depressant with an FDA-approved indication for VMS, and the newcomer on the block, fezolinetant, the one prompting all the new television advertising. Much of the overactivity of NKB acts through a specific receptor, NK3R. Fezolinetant blocks that receptor, lowering the NKB response and returning the body’s thermostat closer to its original balance.

Two recent studies looked at paroxetine and fezolinetant.

Treatment efficacy

The study of paroxetine, a meta-analysis of six prior studies, was published in Frontiers in Psychiatry. The study aimed to quantify the difference between the impact of paroxetine and placebo.

“As the understanding of placebos has grown, we now know that a placebo is more than simply an inert treatment and involves the whole ritual of the therapeutic act itself.”

Cognitive expectancy, a new term for me, is a measure of the placebo effect and can be influenced by many factors, including heightened awareness and concern about side effects, e.g., itching or fatigue, that might unblind a blind trial. That said, the researchers found:

- Placebo reduced episodes by 39%. Reduced hot flashes by 51% (5 fewer episodes), an overall decrease of 12%. Better but a long way from best. In other words, nearly 80% of the paroxetine response could be attributed to a placebo effect, reducing that 51% efficacy to a “true drug effect of 20.74% at most.”

- Paroxetine reduced the severity of symptoms, but 68% of that reduction was also seen with placebo. The true drug effect on severity was “31.71% at most.”

Among their conclusions, they recommend re-evaluating the use of paroxetine as a first-line treatment for VMS and that, at a minimum, the placebo effect should be communicated to the patient as part of the informed consent to treatment. (Yes, informed consent is part of all medical treatment, not just surgical).

The study on fezolinetant comes from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, ICER. [2] They based their conclusions on the published data on efficacy in two Phase III trials and safety from two additional long-term studies. All the participants experienced seven or more episodes of VMS daily.

“58.7% in the fezolinetant 45 mg group achieved a 50% reduction in VMS frequency at week 12 as compared to 36% in the placebo group… More than half of participants (55.1%) in the fezolinetant 45 mg group [reported] VMS frequency was “much better” or “moderately better,”… compared to 31.4% in the placebo group. However, the difference between fezolinetant 45 mg and placebo for VMS frequency at week 12 did not meet the [minimum clinically important difference], a reduction in frequency of >3.57 hot flashes daily.”

Again, better, not best, and the placebo effect accounts for some of that better. In identifying harm, the only concern was an elevation of liver enzymes, more pronounced at higher doses and prolonged use of fezolinetant, but was “generally asymptomatic, resolved on treatment or soon after study, and there were no cases of drug-induced hepatocellular injury with jaundice.”

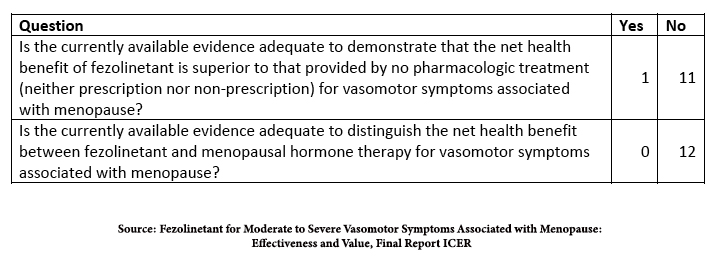

In the studies submitted to the FDA, fezolinetant was more efficacious than placebo in studies conducted in the US; the sole research conducted in China, Korea, and Taiwan involving the lower dose failed to be better than placebo. Here is their conclusion.

Is it worth it?

I will stop mansplaining at this juncture because I am not the one with those hot flashes, so I am a poor judge of the risk-benefit tradeoff.

ICER also included a price point where fezolinetant was better than no treatment; it could not establish a price point compared to hormonal therapy. The current stated price of fezolinetant is $550/month; ICER states that a cost of roughly $200/month makes it better than no treatment at all. I will leave the ladies to make that determination.

It is undoubtedly an option for those women with a contraindication to HRT. Its value to the rest of the symptomatic menopausal women will not be evident for several years. Its value, identified in the studies, will be adjusted to just how many real-world complications it causes and indication creep as physicians offer the treatment to women who feel disabled but have fewer than those seven episodes a day that was the basis for FDA approval.

[1] Severe is characterized as seven or more daily episodes

[2] “Founded in 2006 as a research program at Harvard Medical School, ICER today is an independent non-profit research organization that evaluates the evidence on the clinical and economic value of prescription drugs, medical tests, devices, and health system delivery innovations.”

Sources: Magnitude of placebo response in clinical trials of paroxetine for vasomotor symptoms: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1204163

Fezolinetant for Moderate to Severe Vasomotor Symptoms Associated with Menopause: Effectiveness and Value, Final Report ICER