“Around the world, while people live longer, they live a greater number of years burdened by disease.”

How should we best measure the health of our population? Typically, gains in life expectancy “are recognized as a societal achievement.” But increasingly, some of those gains have come at the cost of chronicity. At the beginning of the 20th century, diabetes was essentially a death sentence. A child diagnosed with diabetes at age ten would die within a few weeks or months. Those deaths contributed to a lower life expectancy for the population. With the advent of an effective medical therapy, insulin, the life expectancy of a patient with diabetes was significantly extended to roughly 61 or better. [1] That improvement raised our population's life expectancy. But insulin did not cure diabetes; it simply made it a manageable chronic illness.

The concept of so-called "healthspan" describes life without disability, years of good health. Healthspan can be estimated using a formula that subtracts, in a weighted manner, for disability. In the example of that patient with diabetes, their healthspan is far less than their lifespan. The number of years they spend disabled by their diabetes will be further influenced by how well they manage their diet as well as medical improvements like the introduction of continuous glucose monitoring and a range of synthetic insulins.

The current research, reported in JAMA Network Open, is trying out the lens of healthspan as an additional, if not better, marker of our population's health than lifespan. Their data comes from the WHO Global Health Observatory, a data repository on the 183 nation members of the UN. It is a population study that comes with uncertainty about the quality of reporting and the need for broad estimates – caution in drawing definitive conclusions is warranted.

In addition to information on gender and the burden of disease, another term for co-morbidities, the researchers used estimates of life expectancy and healthspan. Based on actuarial tables, life expectancy is how long an individual is expected to live at a given age and moment in time. For a newborn, in 2023, it was 79.3 years. Life expectancy is very sensitive to increases in deaths, especially in younger individuals. That little dip in the graph reflects the impact of COVID-19 on our life expectancy when, at its peak, it reduced life expectancy by nearly 3 years.

Healthspan, the years we spend free of disease, is measured by an estimated proxy, health-adjusted life expectancy. This calculation adjusts, that is, deducts for life lived with some disability – the amount subtracted based upon the disease weighted by a subjective measure of disability. For example, two individuals might suffer a myocardial infarction (MI), but one has so significant an injury that they become dependent upon oxygen and are housebound. Their disability will have greater weight than the individual who simply had the MI. Since this is a population study, all of these estimates are aggregates, so while the study may offer up p-value statistics, the findings and conclusions are more qualitative than quantitative.

Results

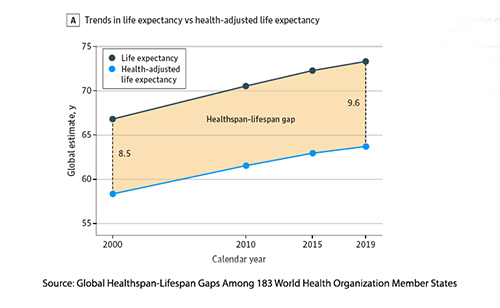

- Worldwide, life expectancy outpaced health-adjusted life expectancy. Global life expectancy increased by 6.5 years compared with

the 5.4-year increase in health-adjusted life expectancy

the 5.4-year increase in health-adjusted life expectancy - The global healthspan-lifespan gap grew by 1.6 years because of “an unequal rise in life expectancy compared to health-adjusted life expectancy.” Globally, “the mean health-adjusted life expectancy of 63.3 years contrasted with a 72.5-year mean life expectancy.” The gap was more pronounced for women than men by 2.4 years

- The healthspan-lifespan gap was linked to increased years lived with disability, primarily from the burden of non-communicable diseases. The differences between the sexes are attributable to the differences in both the burden and life expectancy – both favoring women.

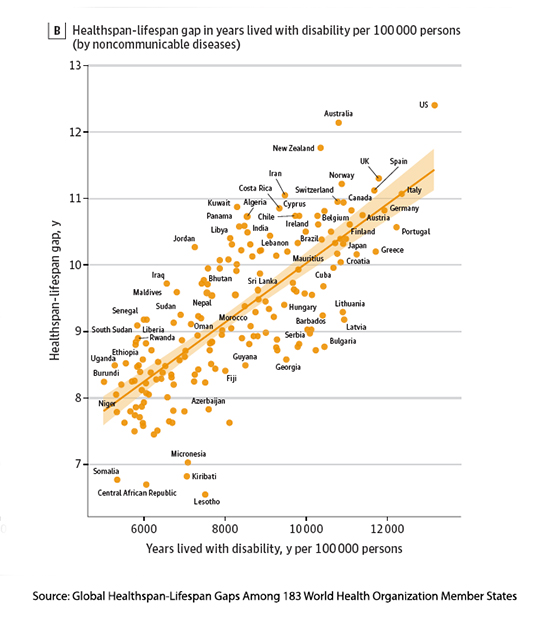

More specifically, for the US

We have the largest healthspan-lifespan gap, rising from 10.9 to 12.4 years 24% larger than expected for its life expectancy and 29% higher than the global average.

We have the largest healthspan-lifespan gap, rising from 10.9 to 12.4 years 24% larger than expected for its life expectancy and 29% higher than the global average.- Women in the US have a healthspan-lifespan gap of 13.7 years, 2.6 years larger than men, and 32% above the global mean for women.

- The US gap reflects a disproportionate rise in life expectancy compared to health-adjusted life expectancy – we live longer with chronic illness.

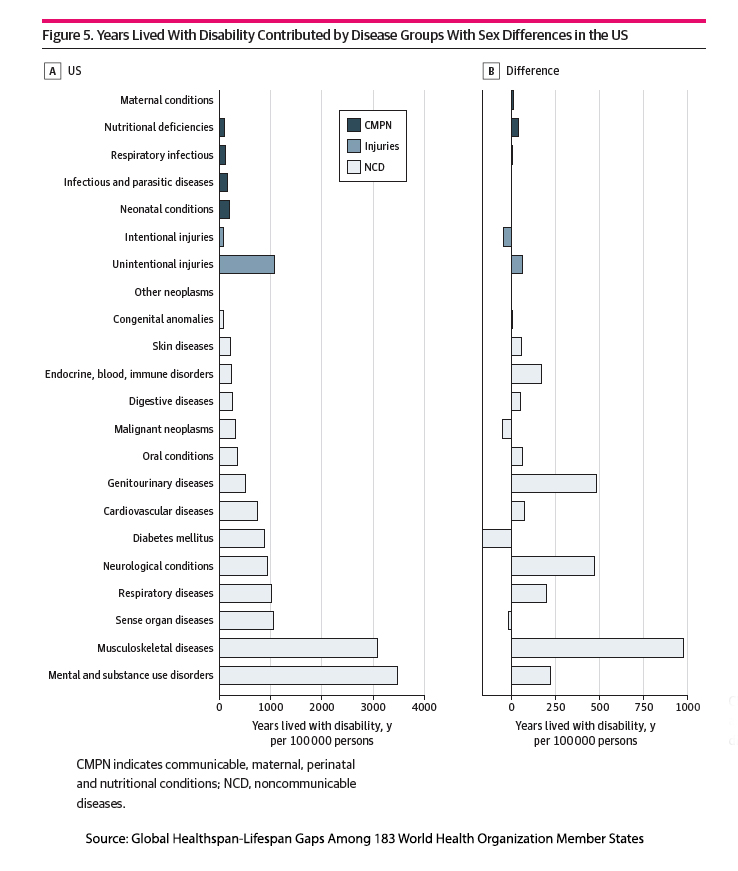

- Leading contributors to years lived with disability in the US include mental and substance use disorders, musculoskeletal diseases, genitourinary diseases, and neurological disorders.

It is worth noting the three conditions in which years lived with a disability did not increase: diabetes, cancer, and intentional injuries. It is hard to parse out whether this is because, say, in the case of intentional injuries, which includes gun and knife mayhem, the individual died  and no longer contributed to disability years, or could it be in the instance of cancer that we are not only living longer but better.

and no longer contributed to disability years, or could it be in the instance of cancer that we are not only living longer but better.

Here is the researchers’ bottom line:

“The US stands out with the largest healthspan-lifespan gap and the greatest non-communicable disease burden. The risk to healthspan is found amplified by longevity and is here recognized to be more pronounced in women. The widening healthspan-lifespan gap is a global trend, as documented herein, and points to the need for an accelerated pivot to proactive wellness-centric care systems.” [emphasis added]

A Disease Paradox

We cure very few diseases, often by removing the offending organ in the case of appendicitis or gall bladder disease, less frequently in some instances for infectious diseases (think Long COVID), and essentially never for degenerative neurological disease or most musculoskeletal disorders. However, the care we do offer in abundance is palliative, defined as care “focused on improving quality of life for people with serious illnesses,” and therefore not wholly restorative.

The individual risk-benefit decisions over therapies made by patients and their physicians are responsible, in part, for that lifespan-healthspan gap – we choose life now with a possible decline in quality later. It is part of our nature, and economists have labeled that bias temporal discounting. That is why, as the authors write, “reduced acute mortality exposes survivors to an increased burden of chronic disease.”

“Wellness centric care” is outside the scope of our health system because while we have an obligation to educate, we are not empowered to mandate. All the pleadings, guidelines, labels, prohibitions, and, frankly, education do not prevent degenerative neurological disease, musculoskeletal disorders, mental and substance abuse disorders, or genitourinary disorders – the top sources of the lifespan-healthspan gap. [2]

“If more people lived healthy lifestyles — eating a balanced, heart-healthy diet, exercising, maintaining a healthy weight and so on — that gap would likely narrow, but we can’t rely on individual “willpower” alone. …“A lot of this relies on the structured environment. When everything relies on our [individual choices], everything works against us.”

- Armin Garmany, lead author

Unfortunately, while a healthy lifestyle is important, diet and exercise will primarily impact cardiovascular disease, perhaps a bit of digestive disease, and malignancies, none of which are the largest determinants of the gap. Whether a nudge, a push, or a mandate, changes to the structural environment are more focused on decreasing the prevalence of a disease, not its chronicity or disability.

The lifespan-healthspan gap is a helpful metric, and the researchers are correct in concluding that,

“Indeed, while the healthspan-lifespan gap is a universal challenge requiring transnational consideration, country-specific profiles invite tailored interventions to maximize equitable and sustainable healthy aging.”

But that doesn’t mean that ranking one country against another is useful or that wringing our hands over the rise in chronic illness is always warranted.

The lifespan-healthspan gap highlights a paradox in modern medicine. While we have extended life expectancy through remarkable medical advancements, we have not equally enhanced the quality of those added years. Addressing this issue requires more than changing our diet and lifestyles; more than changing our healthcare systems. It will require a shift in perspective—embracing a sense of wabi-sabi, the Japanese philosophy of finding beauty in imperfection and impermanence. Aging and chronicity are intrinsic to the human experience, and learning to balance medical intervention with acceptance of life's natural limitations might be just as important as the science itself.

[1] That number is based on the average life expectancy of approximately 76 minus the acknowledged loss of roughly 15 or more years due to juvenile-onset diabetes.

[2] To the extent that genitourinary disorders include birth-related trauma resulting in maternal urinary continence issues, there is still possibly room for “easy” improvement.

Source: Global Healthspan-Lifespan Gaps Among 183World Health Organization Member States JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.50241