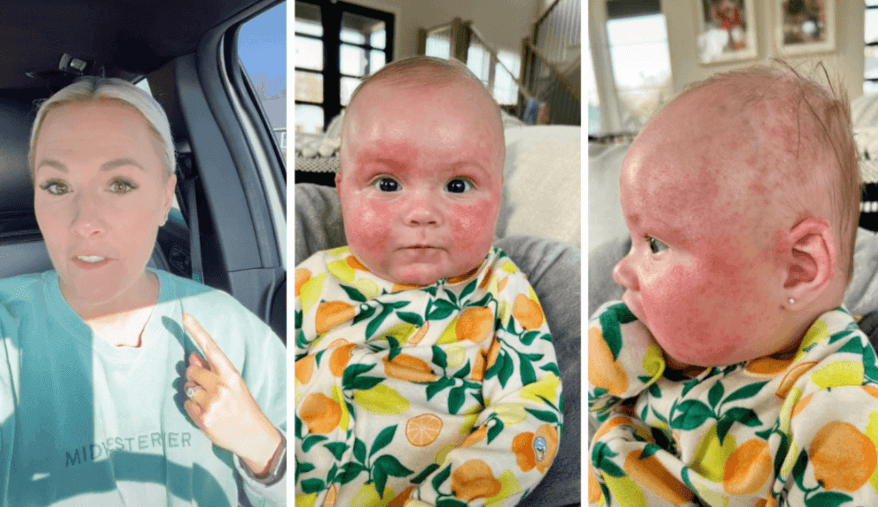

The crisis is long over, but if you were a young family with babies three years ago, scary memories of escalating health worries and retail stores bereft of infant formulas remain. Moms shared horrifying social media images of their babies covered in rashes after being forced to use the only (inferior) formula they could find.

Credit: TikTok

Three years post-crisis, the overriding problem remains. As Fast Company has written:

We still don’t have a resilient or diverse domestic supply, and the government has failed to make any significant progress to prevent a future crisis. We are still just one bacterium away from entering another tailspin due, in large part, to our inability to address the U.S. market failures.

What happened, and why?

An audit released by the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the parent organization of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), is not a pleasant read.

Let us turn back the clock to February 2022. Numerous consumers complained about infants’ illnesses, which the FDA was able to link to the bacterium Cronobacter sakazakii. Several infants were hospitalized and two died after drinking powdered formula made at Abbott Laboratories’ Sturgis, Michigan facility. Abbott initiated a recall as part of a larger voluntary action covering Similac, Alimentum, and EleCare.

The dominant player in the U.S. infant formula market, Abbott controls about 40% of the market share, with the Sturgis facility alone contributing 40% of the company’s total U.S. formula production. Given that more than 3.5 million babies are born in the United States each year, with many relying on formula as a sole or primary nutrition source, the recall’s impact was profound and prolonged, prompting widespread concern among consumers and Congress.

Shelves empty of formula, spring 2022

Delayed actions, inefficiencies and communication failures

Despite receiving reports of problems and whistleblower complaints about safety issues at the Sturgis facility, the FDA’s response was alarmingly slow. In February 2021 — a full year before the FDA issued a public warning — the agency archived a whistleblower complaint instead of forwarding it for investigation, ostensibly due to the fact that the oversight position at the head of the whistleblower complaints division at the National Consumer Complaint Coordinator (NCCC) had been vacant from January 2020 to July 2021.

That October, another whistleblower complaint was sent to multiple senior FDA officials but, due to unreliable policies for escalating such complaints, senior leadership did not receive it until four months later. This delay was attributed to glitches in the FDA mailroom and the absence of a systematic procedure for escalating serious complaints. The former Deputy Commissioner for Food Policy and Response admitted during a congressional hearing that these complaints should have been forwarded up the chain of command much more rapidly.

Inefficiencies in the FDA’s inspection procedures further compounded the issue. During a subsequent inspection at Abbott’s Sturgis facility in September 2021, a new consumer complaint related to a Cronobacter infection was filed but not communicated to the inspection team.

The FDA had no process in place to record and track critical information, which blocks even conscientious investigators from finding out about new complaints during ongoing inspections. Moreover, the FDA’s adverse event reporting structure lagged those of other countries.

Agency policies lacked clarity on which complaints should be communicated to the National Consumer Complaint Coordinator, which resulted in critical reports being mishandled or ignored. For example, some adverse event reports were not forwarded due to alleged resource constraints or misjudgment of the reports’ seriousness, further delaying necessary actions.

It is disgraceful that so many aspects of an important public health problem were allowed to fall through the cracks. The FDA isn’t some startup experiencing growing pains; it has been around since 1906.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted many FDA activities, including inspections deemed mission-critical. The inspection at the Abbott facility, for example, was not conducted until 102 days after the whistleblower complaint was received. This delay was partly due to a pandemic outbreak at the facility and the absence of clear guidelines on how to promptly initiate inspections during public health emergencies. Had the FDA acted sooner, the complaint would likely have identified and addressed the issues at the facility earlier.

Product recalls: Revamped authority and a need for clearer guidelines

The FDA’s authority to mandate recalls also faced scrutiny in the Inspector General’s audit. The Agency did not have specific policies for initiating FDA-required recalls for infant formula, despite having the authority to do so under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. In addition, manufacturers are not required to notify the FDA of positive pathogen test results for undistributed infant formula, which limits the FDA’s ability to address potential health risks preemptively.

During the audit, it also was revealed that Abbott had identified three positive tests for Cronobacter in finished products that were not distributed. The agency claims it only became aware of these results during subsequent inspections, a significant gap in proactive risk management. If manufacturers were required to report such findings, regulators, clinicians and others could better assess and mitigate risks at production facilities and anticipate impending shortages.

The audit of the FDA’s handling of the Abbott infant formula recall uncovered multiple deficiencies in policies and procedures that compromised the agency’s ability to safeguard the infant formula supply chain. Delays in responding to whistleblower complaints, inadequate communication of consumer complaints, lack of timely mission-critical inspections, and insufficient recall authority all contributed to a delayed and ineffective response.

To prevent future crises and ensure the safety of infant formula, the FDA should overhaul its policies and procedures. This would include the writing of clearer guidelines for the timely initiation of inspections; improving protocols to ensure the accuracy of data; streamlining the process for acting on whistleblower complaints; and mandating the reporting of positive pathogen test results for all infant formula products, distributed or not.

This Abbott recall fiasco reminds us of the critical role that regulatory oversight plays in a public health crisis. It is also a reminder that FDA staff often fall short not only in efficiency but also in common sense.

As a 15-year veteran of the FDA, where I served in a variety of capacities, including Special Assistant to the Commissioner (agency head) and the founding director of the Office of Biotechnology, I find some of its actions to be particularly inappropriate and vexing.

For example, several years ago, the FDA sent a formal Warning Letter to a Massachusetts bakery for including “love” in its ingredient list. It said:

Love’ is not a common or usual name of an ingredient, and is considered to be intervening material because it is not part of the common or usual name of the ingredient.

Silly and perhaps not that big of a deal one might think, but an ‘FDA Warning Letter’ is a significant regulatory sanction that would have on it the fingerprints of numerous bureaucrats – bureaucrats responsible for food safety and regulatory compliance who could otherwise have been focusing on legitimate concerns.

Ensuring the safety of infant formula is not just about regulatory compliance; it is about protecting the most vulnerable members of society, and is only one example of numerous systematic problems at the Agency. To regain public trust in its ability to safeguard the nation’s food supply, the FDA must expeditiously implement needed reforms.

Note: A version of this article was previously published by the Genetic Literacy Project.