“The Terrorism Warning Lights Are Blinking Red Again,” according to former CIA Deputy Director Mike Morell, who delivered that message on CBS’ “Face the Nation” and in an article in the journal Foreign Affairs. He cited “a lack of sense of urgency” in both the Biden administration and Congress toward preventing the growing threat of terrorism in the U.S.

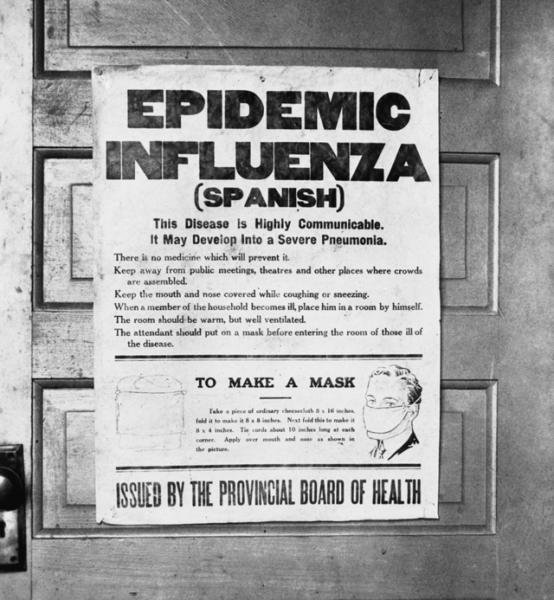

Most people probably associate terrorist attacks with the 9/11 airplane hijackings or the Boston Marathon bombings, but bioterrorism is also a real and growing threat. That was brought home vividly by a fascinating, and terrifying, real-world experiment by an MIT professor and two of his students who re-created a virus identical to the one that caused the devastating 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. During that outbreak, an estimated 500 million people worldwide — one-third of the world’s population at the time — were infected and nearly 50 million died.

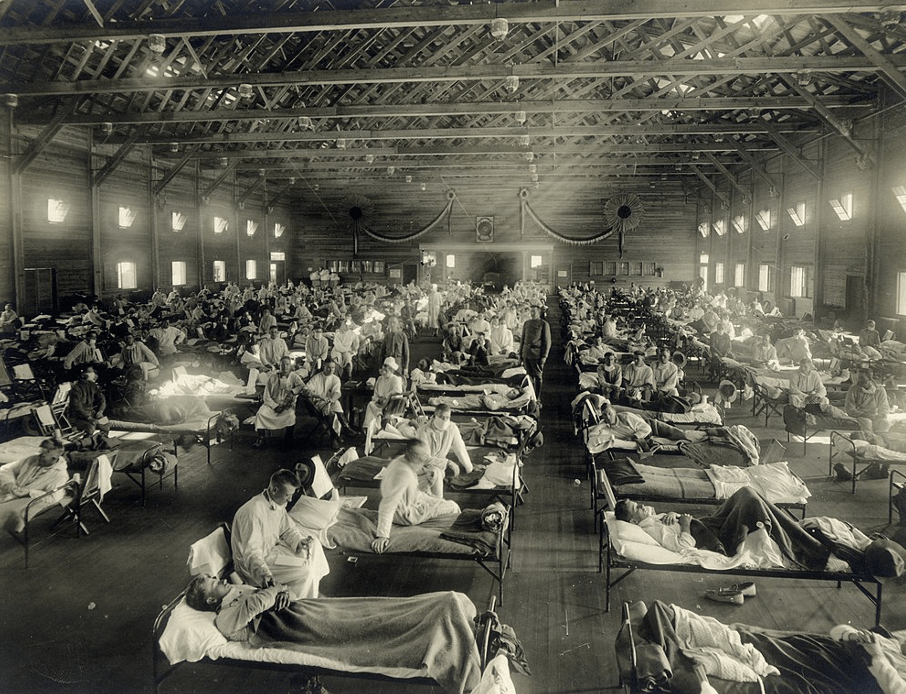

Emergency hospital during Spanish Flu epidemic, Camp Funston, KS Credit: National Museum of Health and Medicine

The experiment, which was conducted by two graduate students of MIT Media Lab Professor Kevin Esvelt under the supervision of the FBI, reveals the vulnerability of the current system. The students found that it is “surprisingly easy, even when ordering gene fragments from companies that check customers’ orders to detect hazardous sequences.”

Security risks

Both the genome sequences of pandemic viruses and step-by-step protocols to make infectious samples from synthetic DNA are now freely available online. That makes it essential to ensure that all synthetic DNA orders are screened to determine whether they contain hazardous sequences that should be shipped only to legitimate researchers whose work has been approved by a biosafety authority.

Terrorists are ingenious and respect no boundaries. Although it was not so long ago, few Americans remember the worst bioweapon attack in U.S. history: After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, letters containing anthrax bacteria began to appear in various parts of the U.S., killing 5 and sickening 17. It created a national scare, with concerns of a larger "attack."

Imagine the havoc if they could create variants of the COVID-19 virus capable of escaping vaccine-induced immunity.

Scientists who synthesize genes (which is accomplished with machines that link together the building blocks to create the genes’ genetic code) and provide them to other researchers are aware of the security risks and the potential for liability: Gene providers who belong to the International Gene Synthesis Consortium (IGSC, “Where Gene Synthesis and Biosecurity Align”) have been voluntarily screening orders since 2009.

But, as MIT's Professor Esvelt observed, these efforts can be compromised under various scenarios: for example, if most of the dozens of non-members don’t screen their orders; if IGSC firms will ship fragments of hazardous sequences without proof of biosafety approval; or if the screening of sequences can be bypassed.

The MIT experiment

To test the effectiveness of current biosecurity practices, the two grad students, overseen by the FBI, conducted a ”red-teaming” experiment. Red-teaming actively tests vulnerabilities in the security infrastructure -- in this case, for screening DNA sequence acquisition and the capabilities of AI tools. It has been used effectively to test cybersecurity, for example, by having ethical hackers emulate malicious attackers’ tactics and techniques against computer security systems.

The students used simple evasive strategies to camouflage orders for gene-length DNA fragments that could be used to recreate the Spanish Flu virus that caused the pandemic of historic proportions. (The flu virus genome consists of RNA, which can easily be made from a DNA template.)

The DNA orders were placed on behalf of an organization that does not perform lab experiments and shipping was requested to an office address that lacks laboratory space, which should have raised suspicion. Alarmingly, 36 out of 38 providers — including 12 of 13 IGSC members — shipped multiple Spanish Flu fragments. Only one company detected a hazard and requested proof of biosafety approval.

But obtaining the potentially hazardous DNA segments was only the beginning of the exercise. The students then demonstrated that standard synthetic biology techniques could be used to assemble the parts to generate infectious virus identical to the one that caused the historic pandemic. (This can be done by using standard biochemical techniques to transcribe the synthetic DNA into viral RNA, which can then be used to reconstitute an intact flu virus when combined with the necessary viral proteins.)

Professor Esvelt takes pains to point out that the fault lies not only with gene synthesis providers, many of whom have been voluntarily screening orders at their own expense. The real problem, he believes, is that governments do not mandate security across the industry and that although it’s a crime to ship at once all the DNA sufficient to generate the entire infectious Spanish Flu virus, it isn’t illegal to ship pieces of it.

Federal intervention

Esvelt cites as a step in the right direction the 2023 Presidential Executive Order 14110, which requires federally funded entities to purchase synthetic DNA only from firms that conduct screening for sequences of concern. The move has strong support from the gene synthesis industry, which has been lobbying Congress for even more stringent regulations.

However, the Executive Order is far from sufficient: Its measures do not reliably detect the types of evasive strategies used by the MIT graduate students. Nor would its strictures prevent front organizations for, say, the Russian, Chinese, or North Korean governments from obtaining DNAs that could be transformed into bioweapons.

According to Professor Esvelt, there are systems that can detect all the evasive strategies used by his students to obtain the complete genome of the Spanish Flu virus, and those systems are now freely available to all DNA synthesis providers and manufacturers of synthesis devices.

It should be noted that there is a Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), an international treaty that bans biological and toxin weapons, but it is toothless. Unlike other arms control agreements, such as the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, the BWC lacks either a robust verification regime or a mechanism for enforcement. And since it applies to the actions of nations, it is unlikely to have any impact on non-state-sponsored terrorists.

A bit of good news: There are already very knowledgeable, highly motivated people working on biosecurity issues, some of the most prominent of whom are at the non-profit Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), which is cochaired by former Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz and former U.S. Senator Sam Nunn (D-GA). A fundamental problem, however, is the absence of strong incentives to adopt widespread, effective security measures.

Bioterrorism is a palpable threat whose mitigation is a shared responsibility between governments and the private sector. They need to act before it’s too late.