Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are quickly digested, triggering insulin release and other regulatory pathways leading to visceral fat accumulation, insulin resistance in the liver and skeletal muscles, and weight gain. The resulting excess body fat and metabolic dysfunction further stimulate inflammatory cytokines, increasing the risk of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes. As a result, SSBs can contribute to the onset of cardiometabolic diseases, i.e., diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD), as well as excess weight gain, which makes its own contribution to diabetes and CVD.

The contribution of SSBs to the onset of diabetes and CVD can be approximated by calculating the population attributable risk (PAR). PAR quantifies the proportion of cases of a disease, diabetes, and CVD, in this instance, in a population that can be attributed to a specific risk factor, SSBs. It is a useful policy tool for identifying areas of intervention and prioritizing resources.

As with any calculation or modeling, there are underlying assumptions. In the case of PAR, there is an assumption that the risk factor is causal, that there is a uniform risk across the population or subgroups, that the risk factor remains stable, not increasing or decreasing over the time interval, and that the calculation excludes confounders. A new study reported in Nature Medicine looks at the Global PAR for SSBs, diabetes, and CVD. Their calculations cannot exclude confounders, so the findings provide uncertain guidance to policy-makers; however, numbers often have a halo of unfounded certainty.

SSBs were any beverage with added sugars and ≥50 kcal per 8 oz serving. They excluded 100% fruit and vegetable juices, noncaloric artificially sweetened drinks, and sweetened milk. The consumption of SSB among “2.9 million individuals from 118 countries representing 87.1% of the global population” came from various surveys and methodologies.

- Globally in 2020, consistent with findings reported in 201812, adults consumed an average of 2.6 8 oz (248 g) servings per week (95% uncertainty interval (UI) 2.4–2.8)

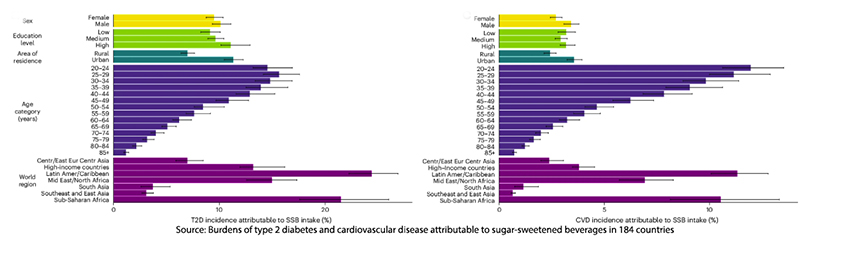

- Globally, regionally, and nationally, men had modestly higher energy-adjusted SSB intake than women.

- SSB intakes were generally higher in all world regions at younger than older ages.

- Contrary to the common narrative of SSB consumption in the US, SSB intakes were higher among the more educated adults in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean and lower among more educated in the Middle East and North Africa.

The PAR for SSBs in the onset of type 2 diabetes was estimated at 9.8%; for cardiovascular disease, the PAR was 3.1%. The PAR associated with diabetes was slightly greater in men, the higher-educated, the urban, and peaked in the 45-49 age group. The PAR for CVD followed the pattern of diabetes for gender and urbanicity, but education played no role, and age was an increasingly smaller factor for CVD’s PAR.

“Globally, we found that 2.2 million new cases of T2D and 1.2 million new cases of CVD in 2020 were attributable to SSBs—representing about 1 in 10 new T2D and 1 in 30 new CVD cases.”

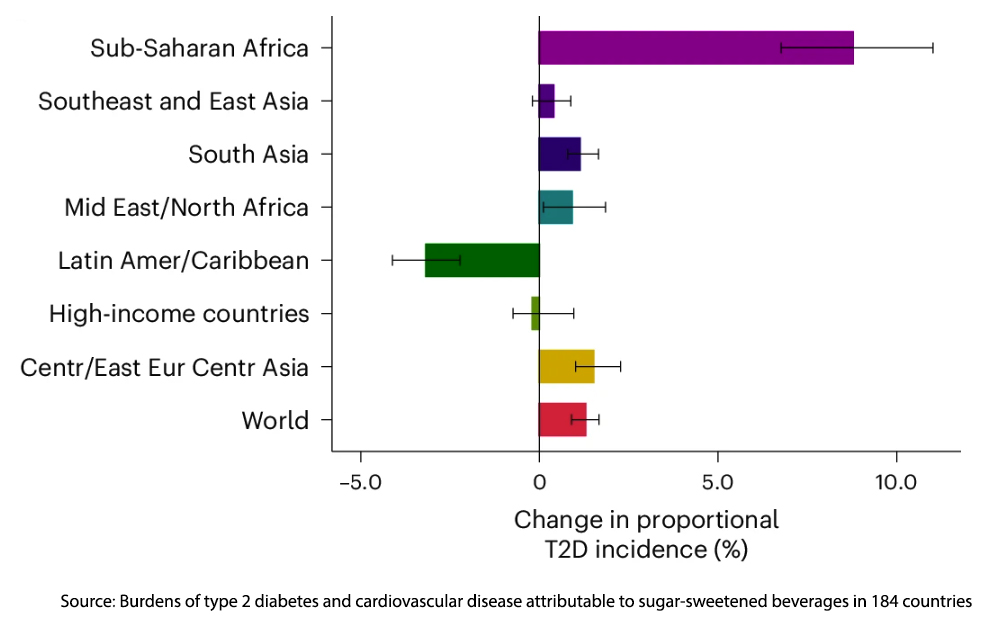

Of course, from a policy perspective, the most frequently applied method is taxation and education. Mexico was the first country to put an SSB tax in place, resulting in a 6.3% reduction in expected purchases and a 16.2% increase in water purchases. Despite that, the “greatest absolute numbers of new [type 2 diabetes] cases attributable to SSBs were in Mexico. How could that be?

The researchers offer up commercial interests – an easy target. As they write,

“Mexico faces industry opposition to its soda tax, including industry-supported reports questioning the efficacy of the tax to reduce intakes and suggesting harms to jobs and the national economy, as well as amplified marketing through advertising, price reductions and bonus products.”

Despite all of those foreseeable actions on the part of commercial interests, the tax effectively reduced consumption – it just didn’t reduce the incidence of diabetes. The researchers point to two further factors.

First, in addition to the declines being inadequate (and the silent thought that a higher tax will further reduce consumption), other risk factors in the lifestyle, including consumption of highly refined grains and physical inactivity, are at play. Moreover, in considering the rise in SSB consumption in Sub-Saharan Africa, they point to a growing educated middle class who are transitioning to a “Western diet.” For the mathematically inclined, the attributed risk of any factor is impacted by the contribution of other factors. For example, the role of SSBs in CVD competes with the role of smoking, hypertension, and cholesterol for prominence. A population that has a large population of heavy smokers may repress any effect that can be statistically identified as coming from SSBs.

First, in addition to the declines being inadequate (and the silent thought that a higher tax will further reduce consumption), other risk factors in the lifestyle, including consumption of highly refined grains and physical inactivity, are at play. Moreover, in considering the rise in SSB consumption in Sub-Saharan Africa, they point to a growing educated middle class who are transitioning to a “Western diet.” For the mathematically inclined, the attributed risk of any factor is impacted by the contribution of other factors. For example, the role of SSBs in CVD competes with the role of smoking, hypertension, and cholesterol for prominence. A population that has a large population of heavy smokers may repress any effect that can be statistically identified as coming from SSBs.

A more salient point is that there is a lag as differing nutrition alters our health; more importantly, there is a generational component. Tobacco use declined as those raised in a time and place where smoking was “normalized” died out and was replaced by a generation raised and educated on the health risks of smoking. They are correct that even this small impact of SSBs on our cardiometabolic health will require “concerted multigenerational efforts over many years.”

While sugar-sweetened beverages are undeniably a contributing factor to the global rise in type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, the story is far from simple. Tackling their impact requires more than taxes and education—it demands a holistic strategy that blends personal responsibility and policy intervention. It begins with a more realistic understanding of its role and impact.

Source: Burdens of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease attributable to sugar-sweetened beverages in 184 countries Nature Medicine DOI: 10.1038/s41591-024-03345-4