Fourteen years ago, Michael Pollan published Food Rules: An Eater’s Manual which contained some rule-like aphorisms to guide our dietary choices.

“Avoid food products that contain more than five ingredients. …

Avoid food products containing ingredients that a third-grader cannot pronounce.”

― Food Rules: An Eater's Manual

A new study in Nature Food has applied a machine learning algorithm (what else?) to over 50,000 real-world grocery items from Walmart, Target, and Whole Foods [1] to bring Pollan’s warning to life. Acknowledging that measuring food processing is challenging due to inconsistent classification systems, poor reproducibility, and conflicting health risk findings, the researchers tried to classify the processing degree based on food ingredients. They correlated their findings with the NOVA food-processing classification, an increasingly accepted categorization describing the degree to which foods are processed, not their nutritional content or value.

“Nutrition science, which after all only got started less than two hundred years ago, is today approximately where surgery was in the year 1650—very promising, and very interesting to watch, but are you ready to let them operate on you? I think I’ll wait awhile.”

― Food Rules: An Eater's Manual

While Pollan may have meant those scientists creating ultra-processed foods, his thinking also applied to those scientists doing nutritional studies, including this one. But before throwing out the baby and the bathwater, there are some nuggets of insight.

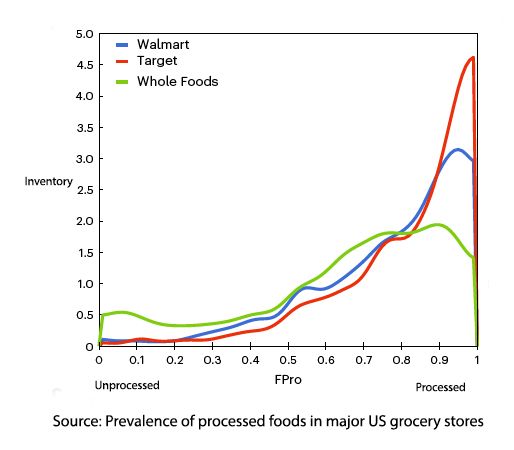

All three stores display a similar overall pattern—with most products falling into the ultra-processed category and relatively few minimally processed items. Despite this common trend, some key differences emerge: Whole Foods carries more minimally processed options and fewer ultra-processed products, while Target has a particularly large share of ultra-processed items. Notably, although minimally processed foods occupy a smaller portion of total inventory, they likely account for a disproportionately larger share of actual purchases.

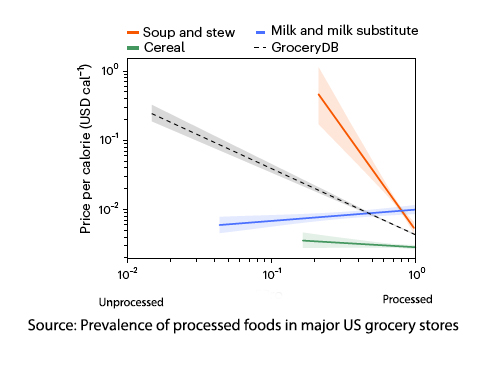

All three stores display a similar overall pattern—with most products falling into the ultra-processed category and relatively few minimally processed items. Despite this common trend, some key differences emerge: Whole Foods carries more minimally processed options and fewer ultra-processed products, while Target has a particularly large share of ultra-processed items. Notably, although minimally processed foods occupy a smaller portion of total inventory, they likely account for a disproportionately larger share of actual purchases.- A 10% increase in the calculated degree of ultra-processing corresponded to an overall 8.7% drop in the price per calorie. Ultra-processed foods are less expensive and more calorie-dense. To add complexity, the impact of ultra-processing on price varied widely with the food category – a 24% drop for soups, 1.2% for cereals, and a price increase for those plant-based milks (which are more processed than cow’s milk). Categories such as jerky, popcorn, chips, bread, biscuits, and mac and cheese show limited processing choices for consumers. While the nutritional “scolds” point

to the addictive nature manufactured into processed foods, few point to the price subsidies on additives, i.e., sugar, that contribute to the lower price per calorie for foods requiring processing than foods without that subsidy, fruits and vegetables, that require no additional inputs.

to the addictive nature manufactured into processed foods, few point to the price subsidies on additives, i.e., sugar, that contribute to the lower price per calorie for foods requiring processing than foods without that subsidy, fruits and vegetables, that require no additional inputs.

“If it came from a plant, eat it; if it was made in a plant, don’t.”

― Food Rules: An Eater's Manual

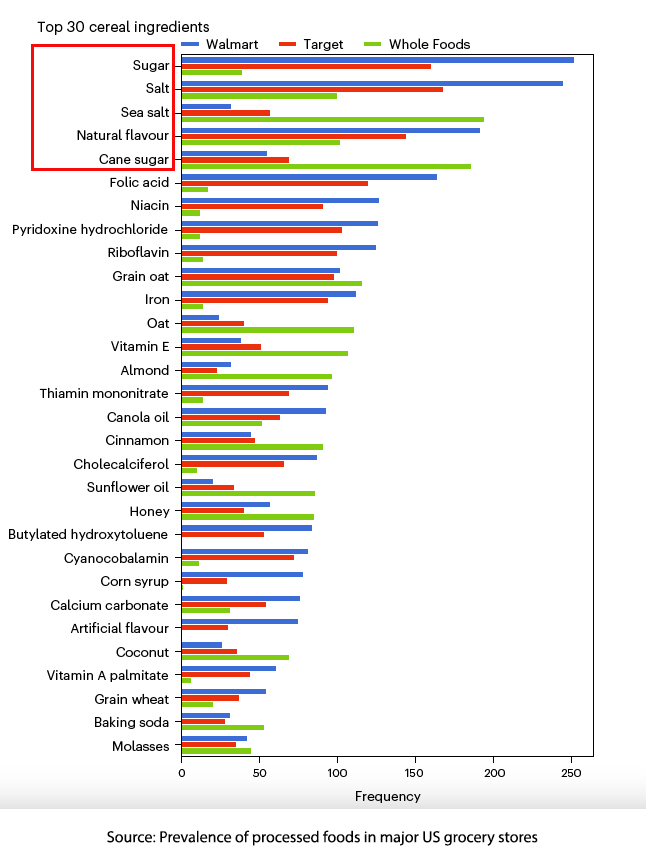

Not surprisingly, there are differences in the product offerings of the three stores when examining the ingredients. [2] The researchers point to cereals where Whole Foods offers cereals with lower sugar content, fewer artificial and natural flavors, and fewer added vitamins. In contrast, Walmart and Target products more often include corn syrup as a sweetener. However, there is a sleight of hand at work here. Take a look at those cereal ingredients boxed in red.

While it is true that Whole Foods uses less “sugar,” they use far more “Cane sugar,” far less “salt,” and more “sea salt.” [3] This gets at one of the flaws in all these models. In the reductionist world focused on processing, sugar and cane sugar, salt, and sea salt are very different products; however, in a reductionist world focused on biological distinctions, they are all sugar or salt – there is no nutritional difference. In this instance, Pollan’s aphorism, while pithy, breaks down when more carefully examined.

“Avoid food products containing ingredients that no ordinary human would keep in the pantry. Ethoxylated diglycerides? Cellulose? Xanthan gum? Calcium propionate? Ammonium sulfate? If you wouldn’t cook with them yourself, why let others use these ingredients to cook for you?”

― Food Rules: An Eater's Manual

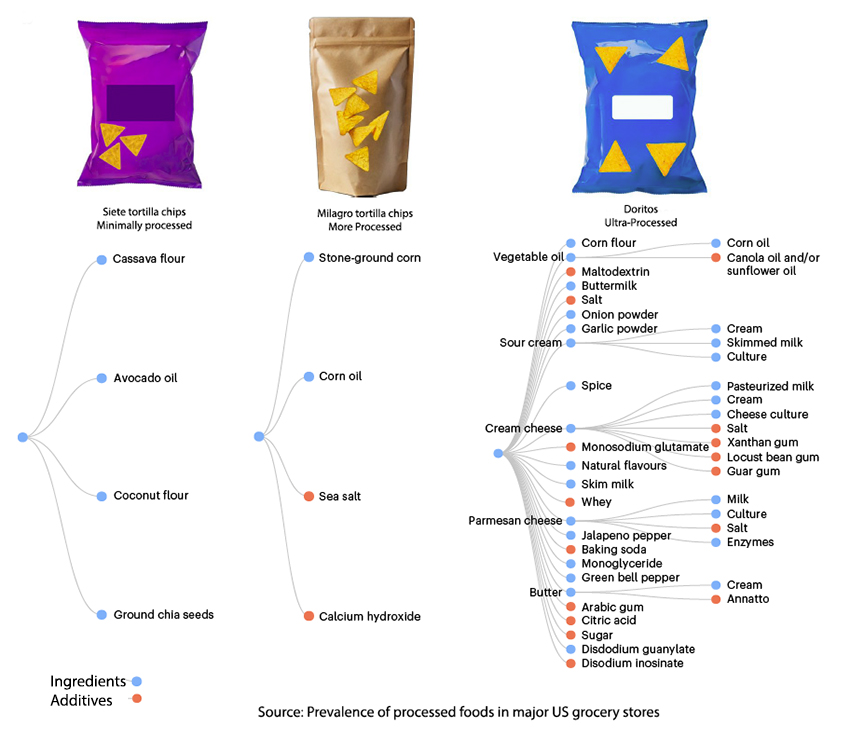

The researchers developed ingredient trees based on the legal requirement that the list of ingredients is presented in descending order of the amount used in the final product.

First, we must point out that the Siete tortilla chip is in apparent violation of 21 CFR § 102.41, which requires the chip to be made from corn masa dough, which must be nixtamalized. Nixtamalization refers to a traditional process of treating corn with an alkaline solution (water and calcium hydroxide – a chemical or, in some instances, wood ash). The Dorito makes no claim of being a tortilla chip.

Should we really consider salt, sea, or otherwise an additive, or is it an ingredient – while recipes I have used at home ask me to add salt, it is listed as an ingredient. And what about whey, a natural component of milk – does its separation from curds alter its value to the degree that we should deride it as an “additive.”

Moreover, not all additives contribute equally to ultra-processing. In the researchers’ consideration of both minimally and ultra-processed cheesecakes, both contained the additives, xanthan gum, guar gum, locust bean gum, and salt; however, it was the polysorbate 60, an emulsifier, and corn syrup, as a sweetener, that pushes one cheesecake into the UPF danger zone.

The researchers have offered a means of evaluating, at scale, the relative processed nature of foods. From the health perspective, they have identified possible risks for the “at-risk danger warriors” but have failed to determine nutritional value. And while some of our shopping choices are based on avoiding risk, shouldn’t our food shopping be based on nutritional value – especially for those at-risk danger warriors who find themselves simultaneously in the “food as medicine” tribe?

In the end, the researchers hope,

“… translating this wealth of data into an actionable scoring system, [enables] consumers to make healthier food choices and embrace effective dietary substitutions, without overwhelming them with excessive information. … Providing access to this information could empower consumers to select less-processed items, yet food labels often prove difficult to interpret due to unrealistic serving sizes and narrow health claims.”

I spent a few moments rummaging through the database the researchers have created, which is available in a more user-friendly version here. Roughly 10% of the food products classified as ultra-processed included the term “organic” in its labeling. Labels are where the truth about nutrition and processing goes to die, as special interests of all views fight for a place to nudge purchases. Or, as Michael Pollan more succinctly wrote,

“For a product to carry a health claim on its package, it must first have a package, so right off the bat, it's more likely to be processed rather than a whole food.”

― Food Rules: An Eater's Manual

Last word to the researchers,

“…multiple factors drive the range of choices available in grocery stores, from the cost of food and the socioeconomic status of the consumers to the distinct declared missions of the supermarket chains: ‘quality is a state of mind’ for Whole Foods Market and ‘helping people save money so they can live better’ for Walmart.”

Whether it’s Whole Foods pretending cane sugar is virtuous or Walmart bragging about “helping you live better” by selling the cheapest calories, the real takeaway isn’t about avoiding processing—it’s about understanding what’s actually nourishing. So, keep Pollan’s rules handy, but maybe temper them with some skepticism and a pinch of salt, sea or otherwise. It’s not about dodging “unpronounceable” ingredients—it’s about finding real value, nutrition, and maybe a cheesecake that doesn’t need a chemistry degree to decode.

[1] They are #1, #13, and #28 among the top grocery chains in the US in 2024

[2] Some food categories, such as pizza, mac and cheese, and popcorn, are highly processed in all stores

[3]Walmart had the most sugar, 307, but Target and Whole Foods were essentially tied at 229 and 225. Whole Foods had the most for salt at 293, followed by Walmart at 277 and Target at 225.

Source: Prevalence of processed foods in major US grocery stores Nature Food DOI: 10.1038/s43016-024-01095-7